November 2, 2020

Open Access

Locating and Accessing Plain Language Summaries

VP, Global Corporate Sales, Wiley/Oxford, United Kingdom

Plain language summaries (PLS) are the logical extension of the drive to open science. Science that is accessible to a broad community carries with it a responsibility to communicate effectively with that broad community audience. Particularly in medicine, as we continue toward truly patient-centric treatment and the research behind it, there is an imperative to support informed healthcare decisions by improving our ability to communicate science in a digestible format to a nontechnical audience.As we continue toward truly patient-centric treatment and the research behind it, there is an imperative to support informed healthcare decisions by improving our ability to communicate science in a digestible format to a nontechnical audience. Including PLS in pharmaceutical industry-sponsored articles is an essential part of patient centricity within the industry. However, the responsibility to improve science communication to a broad audience lies with all authors, regardless of the funding source of the research.

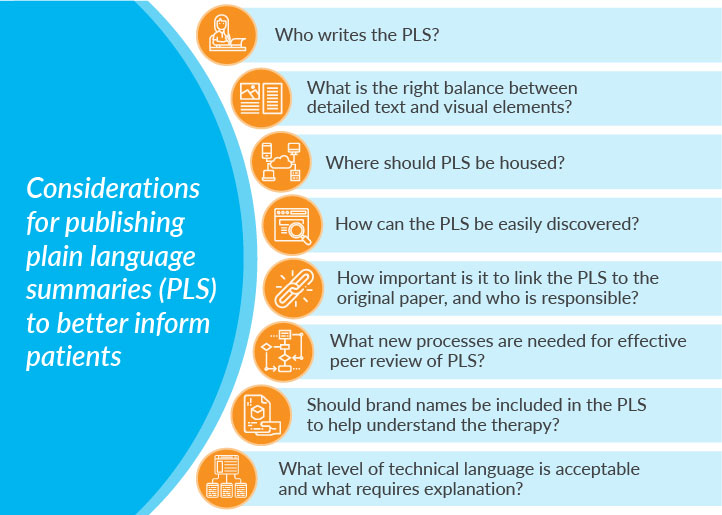

Considerable work is underway within the medical publication and communications world to deliver clear, nontechnical, engaging content. Important questions are being addressed, such as who writes the PLS and how? What is the right balance between visual elements, such as infographics and detailed text?

While progress is being made in producing digestible and engaging content, an often-overlooked principle is accessibility. Where should PLS be housed? How do we ensure PLS can be found by those who need them? How important is it that PLS be linked to the original research paper for context? Whose responsibility is it?

Discoverability of PLS with a focus on biomedical research journals was investigated recently and presented at the 2019 European Meeting of The International Society for Medical Publication Professionals.1 The results showed that almost all journals publishing PLS made that content freely available. However, there was inconsistency in terminology, location, and other factors that could present challenges for lay audiences when searching for this content.

The British Journal of Dermatology has published PLS since 2014.2 The journal immediately recognized the importance of discoverability and deployed tools that remain valid today. Prominent links to PLS on the article’s web page are used to ensure viewability by and availability to those searching for PLS via external search engines. The PLS are made freely available to all browsers, and a patient-access program facilitates access to the full paper.

Enhancing content is a well-recognized driver of discoverability for research output. Studies conducted on Wiley Online Library have established that interactive, concise, easy-to-digest, enhanced formats help to drive audience engagement and increase the impact of publications. Given the long experience of some journals and the data that support enhancing PLS to drive discoverability, why is it so hard to gain consistency in processes for publishing and hosting PLS? For example, the addition of a video component increases Altmetric attention scores almost 5 fold and full text views on the Wiley Online Library by more than 100%.3 At Wiley, discovery packages are readily available to support publication planning and benefit from early discussion with the target journal.4 These principles also apply to PLS.

Given the long experience of some journals and the data that support enhancing PLS to drive discoverability, why is it so hard to gain consistency in processes for publishing and hosting PLS?

There are considerations around efficient and effective peer-review processes. Peer review was designed to validate the quality, relevance, and significance of published research. Within that context, new processes are required for PLS to facilitate simultaneous review and to avoid duplication of effort. Importantly, guidance is required on the reviewer’s purpose and role in relation to the PLS.Ongoing education and discussion are required to develop the processes and guidance necessary to support the publication, hosting, and discovery of PLS. There are potential conflicts and areas of confusion in the language required in an effective PLS. What level of technical language is acceptable, and what requires explanation? Should brand names be included to help the lay person understand the therapy being evaluated? If so, would the reviewer’s brand perception impact his or her perception of the PLS? These potential perception challenges should be addressed through open communication and education within the author and peer reviewer community.

Ongoing education and discussion are required to develop the processes and guidance necessary to support the publication, hosting, and discovery of PLS. In the meantime, researchers seeking to publish research with PLS should consult early with the journal to plan for the inclusion of enhanced content and for simultaneous peer review of the PLS.

References

- Fitzgibbon H, et al. Where are biomedical research plain-language summaries (PLS)? Poster presented at the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) 2019 European Meeting; London, UK; January 22-23, 2019. Poster 20.

- Anstey A. Plain language summaries in the British Journal of Dermatology: connecting with patients (editorial). Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1-3.

- John Wiley & Sons. Share your research with videos. 2020. Accessed August 11, 2020.

- Wiley Corporate Solutions. Article Discovery Package. Published 2020. Wiley. Accessed October 16, 2020.

August 10, 2020

Transparency

Diversifying Journal Ratings to Promote Transparency and Reproducibility

Academia is, at best, a conflict between how scientific research is expected to work in an idealistic world and how it actually works with careers that depend on getting published, getting funded, and getting hired.

This conflict is perfectly demonstrated by a study conducted by Melissa Anderson and her colleagues in 2007,1 in which they asked researchers how they felt about the “norms” of scientific research (eg, open sharing of evidence, disinterested skepticism of findings, and quality over quantity) versus “counter norms” (eg, being secret, dogmatic, and focused on quantity). A large majority of researchers responded that they endorsed the norms [of scientific research].A large majority of researchers responded that they endorsed the norms over the counter norms, and a slightly smaller majority reported practicing the norms. However, when asked what their peers or colleagues practiced, most reported that they were secretive, dogmatic, and focused on quantity. This dissonance between ideal expectations and practical reality reveals an uncomfortable truth: being a team player in science is perceived as career suicide.

Entering this milieu are large-scale efforts to systematically estimate how reproducible scientific research has become. Though replication is essential to how science is designed to work, it is seen as boring and unrewarding by many researchers, journals, and funding agencies, because it’s not about making a new discovery (the reason why many scientists entered the profession, and why funding agencies give money to conduct research) but rather about confirming previously suggested findings. Nevertheless, the scientific method is designed to work by testing prespecified, precise hypotheses that have been identified through preliminary, exploratory work. Because there is incentive to present only the most surprising and cutting-edge findings with tools that are designed for rigorous experiments with large sample sizes, we can unintentionally present these preliminary findings as if they were confirmations, which makes them seem both rigorous and new. This combination of messy, opaque research and attention given to many small studies leads to findings that cannot be replicated when others try to conduct the same experiments.By aligning ideals (openness, reproducibility, and quality) with concrete rewards (getting published, funded, and hired), we can make sure that these ideals are followed as they were intended.

Fortunately, there is a road map for fixing these issues. By aligning ideals (openness, reproducibility, and quality) with concrete rewards (getting published, funded, and hired), we can make sure that these ideals are followed as they were intended.

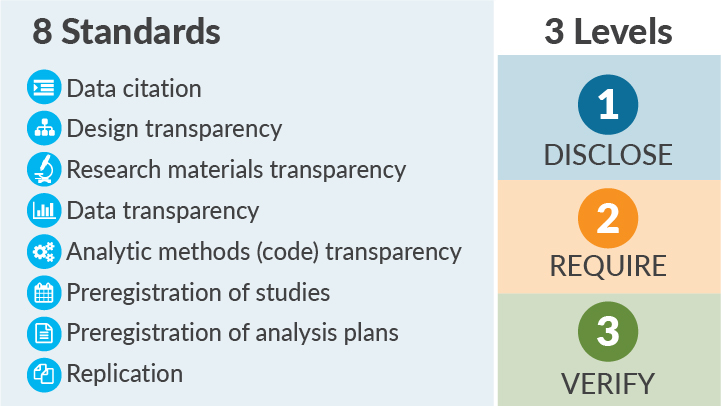

The Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines (Figure 1) provide such a roadmap.2 The TOP Guidelines provide specific and concrete policy language for funders and publishers to follow when prioritizing rigor over novelty and reproducibility over ephemera. The Guidelines include 8 standards that can be implemented in policies, classified in 3 Data Transparency Levels of increasing rigor: Level 1 indicates a policy that requires disclosure of a practice (such as whether the data are available or whether the work was prespecified); a Level 2 policy mandates transparency; and a Level 3 policy is a verification check that the research and reporting standards outlined in Levels 1 and 2 are done well. A fourth level, “Level 0,” represents the status quo: encouraging transparency but being ineffective at spurring change or saying nothing.

Figure 1. The TOP Guidelines include 8 standards and 3 levels.

The TOP Guidelines have been around since 2015, and more than 5,000 journals have become signatories. Unfortunately, too many journals are still evaluated on metrics that focus on the novelty of the work they publish and not on transparency or rigor. These “Impact Factors” were created to show how often publications in the journal are cited, which is important when measuring where novel data are published, but has no bearing on quality, rigor, or the ability to reproduce a finding.

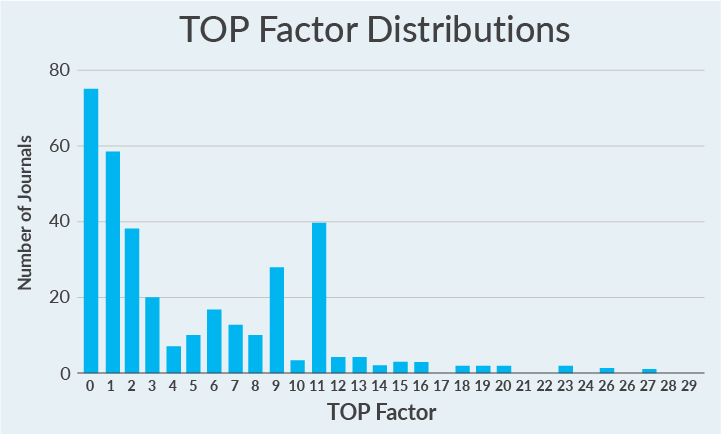

...most journals evaluated so far have taken no concrete steps toward promoting open science practicesThe TOP Factor is an alternative to this dilemma. The TOP Factor is a metric that sums up stated journal policies and provides a clear rating based on a possible 29 points: up to 3 points are given for each of the 8 TOP Guidelines adopted in a journal’s policies, and additional points are given for offering a publishing model called Registered Reports or signalling when open practices are occurring with badges.3,4

Out of a possible 29 points, most journals evaluated score 0 (Figure 2). That’s right—most journals evaluated so far have taken no concrete steps toward promoting open science practices.

Figure 2. TOP Factor scores for 346 journals' policies included to date. Scores can range from 0 to 29; actual scores range from 0 to 27; mean rating = 4.9; median rating = 3; mode rating = 0.

To further familiarize researchers with these initiatives, TOP Guideline Levels are currently being displayed on FAIRsharing data policy pages and on the Web of Science Master Journal List.5,6 FAIRsharing is a searchable resource that organizes data standards, databases, and data policies to help make them discoverable to others. Each data policy page displays information on the TOP Data Transparency Level and TOP qualifying comments. The Web of Science Master Journal List provides TOP data for each of the TOP Factor standards. Visibility of the TOP Guidelines and the TOP Factor can also increase when journals convey how they implement the TOP Guidelines.

Despite the lack of progress by some in implementing open science practices, there are many examples of journals with strong policies. I encourage you to take a look for journals in your discipline and, for those that fall behind, advocate for the implementation of basic measures to promote transparency over fluff.7

References

- Anderson MS, Martinson BC, De Vries R. Normative dissonance in science: Results from a national survey of US scientists. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2007;2(4):3-14.

- Nosek BA, Alter G, Banks GC, et al. Promoting an open research culture. Science. 2015;348(6242):1422-1425.

- Center for Open Science. Registered Reports: Peer review before results are known to align scientific values and practices. 2020. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Center for Open Science. Open Science Badges enhance openness, a core value of scientific practice. 2020. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- FAIRsharing. FAIRsharing policies: A catalogue of data preservation, management and sharing policies from international funding agencies, regulators and journals. 2020. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Web of Science Group. Master Journal List. 2020. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Center for Open Science. Top Factor. 2020. Accessed July 29, 2020.

October 16, 2019

Transparency

Transparency Matters for Reproducibility

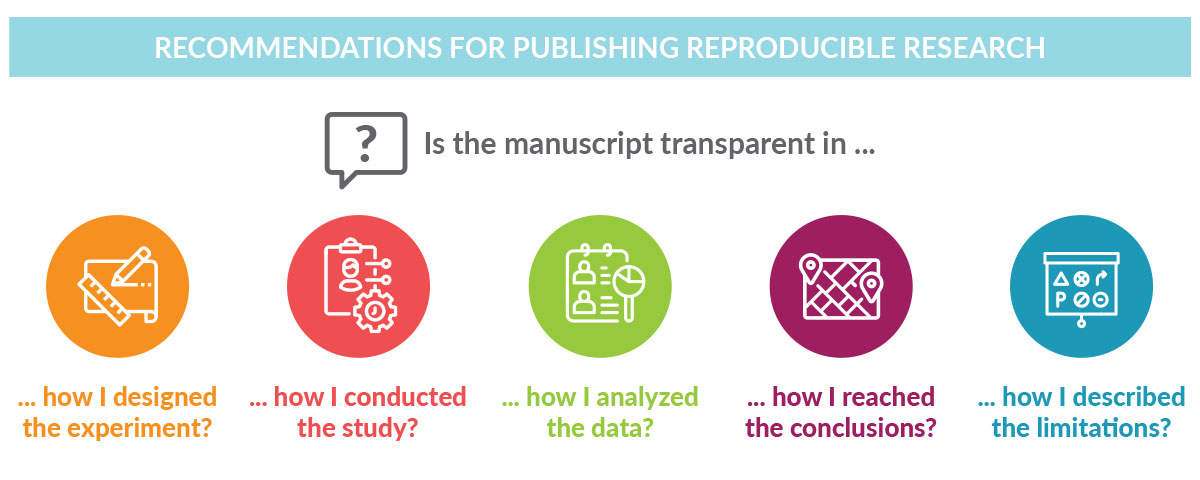

Researchers frustrated by trying to reproduce results from peer-reviewed publications know firsthand the importance of transparency. Transparent reporting of research methods and results in peer-reviewed journals ensures scientific advancement by stimulating research, avoiding duplication of research efforts, and allowing the validation of findings.Transparent reporting of research methods and results in peer-reviewed journals ensures scientific advancement by stimulating research, avoiding duplication of research efforts, and allowing the validation of findings. Through transparent reporting, sponsors of clinical trials not only fulfill legal and regulatory requirements,1-3 but also build the trust of interested readers, including scientists, clinical trial investigators, and, importantly, patients.

Like transparency, reproducibility has multiple definitions depending on the context and this can lead to confusion.4 Goodman and colleagues propose that the concept of reproducibility should be applied to the methods, results, and conclusions of a given study.4 For a clinical or preclinical scientific study to be reproducible, the report of the findings must be transparent about how the study was conducted, how the data were analyzed, and how the conclusions were drawn. Enabling reproducibility gives researchers a window into the research process, making it easier for them to adapt methodology to their own research initiative and build on earlier findings.

Despite its importance, the reproducibility of basic life science investigations has been questioned in recent years by scientists themselves. Studies have shown that scientists have difficulty reproducing their own data and data from other researchers.5,6 Despite its importance, the reproducibility of basic life science investigations has been questioned in recent years by scientists themselves. Given that drug development relies heavily on the published results of preclinical studies, designing clinical trials based on irreproducible data can affect the success rate of those trials. Although challenges in reproducing data are likely due to multiple factors such as differences in laboratory environments, reagents, models, and/or insufficient statistical analyses, these findings highlight the importance of well-designed experiments with appropriate controls that account for investigator bias. Accurate reporting of preclinical data, including the methodological details, helps ensure reproducibility across multiple models while enabling the advancement of the most promising drug candidates to clinical development.

Journals and professional organizations have developed guidance on data reporting to support the development of transparent, and hopefully reproducible, research reports. For example, the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB), the largest coalition of biomedical researchers in the United States, developed consensus recommendations7 for enhancing reproducibility of research findings. These guidelines promote the reporting of research in a transparent and reproducible manner to ensure that research efforts advance science, medicine, and, ultimately, patient care. Nature journals publish a reporting summary document alongside every life sciences manuscript with detailed information on experimental design, reagents, and analyses8; similar guidance exists for clinical research. Researchers conducting randomized trials should look to the CONSORT statement for practical recommendations and detailed guidance on information that should be included in each section of their manuscript.9 The EQUATOR Network maintains a comprehensive searchable database of reporting guidelines wherein researchers at all stages, from those performing preclinical animal studies to those conducting economic evaluations, can find guidance on the most appropriate information to include when developing a manuscript. These guidelines promote the reporting of research in a transparent and reproducible manner to ensure that research efforts advance science, medicine, and, ultimately, patient care.

Resources for guidance on transparent reporting |

|

|---|---|

Source |

Types of Studies Included |

Enhancing Research Reproducibility: Recommendations from FASEB |

Preclinical studies |

Towards greater reproducibility for life-sciences research, an editorial in Nature |

Preclinical studies |

CONSORT 2010 statement , by Kenneth Schulz and colleagues |

Clinical studies |

Comprehensive database of reporting guidelines across preclinical and clinical research |

|

Complementing these various organizational and journal efforts, Medical Publishing Insights & Practices (MPIP) aims to elevate trust, transparency, and integrity in reporting the results of industry-sponsored clinical research. At the core of MPIP’s efforts is Transparency Matters, a global education and call-to-action platform. Within Transparency Matters is What Transparency Means to Me, a space for those involved in reporting research to share their perspectives on how transparency can best be achieved when disclosing data. All are invited to read the researcher perspectives and show their commitment to transparency by joining the conversation and sharing their voice on the What Transparency Means to Me Quote Board.

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical Trials Registration and Results Information Submission. Final Rule. 42 CFR Part 11. Fed Regist. 2016;81(183):64981-65157.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007: Public Law 110–85. 121 Stat. 823. September 27, 2007.

- The European Parliament and The Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) No. 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/20/EC. 2014. pp L158/1-L158/76.

- Goodman SN, Fanelli D, Ioannidis JP. What does research reproducibility mean? Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(341):341ps12.

- Baker M. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature. 2016;533(7604):452-454.

- How can scientists enhance rigor in conducting basic research and reporting research results? A white paper from the American Society for Cell Biology. American Society for Cell Biology. Published 2015. Accessed January 21, 2019.

- Enhancing research reproducibility: recommendations from the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB). Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. Published January 14, 2016. Accessed January 21, 2019.

- Announcement: Towards greater reproducibility for life-sciences research in Nature [editorial]. Nature. 2017;546(7656):8.

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332.

August 29, 2019

Open Access

MPIP Tackles Barriers to Open Access Through Latest Initiatives

In our efforts to identify and unlock barriers to increased adoption of open access (OA) by industry, Medical Publishing Insights & Practices (MPIP) identified two issues MPIP could focus on and make a difference:

- A general lack of understanding of what OA is, why it is important, and how it works

- A lack of easily accessible information on OA options available for publication of industry-funded research

To these ends, MPIP has worked to provide resources to advance understanding of OA with the ultimate goal of expanding access to research results and promoting transparency.

In late 2018, we launched our Open Access Reference Site to answer frequently asked questions on OA. Earlier this year, we collaborated with societies on educational webinars to share perspectives on this topic (see below). These initial efforts were designed to tackle the first barrier: Help address gaps in awareness and understanding.

A bespoke tool with information for authors of industry-funded research and the publications professionals who assist them did not exist.

In this blog post, we share our progress on the second barrier. Authors wishing to publish their research on OA terms may face difficulty in finding relevant policy information on journal websites. Various tools are available to help authors more easily find OA policies; however, these tools generally contain information most useful for authors with funding from non-profit organizations and government agencies. OA options can vary by journal and be more restrictive for authors of industry-funded research. Because these restrictions may not be reported on a journal’s website, authors may need to contact the journal directly to understand the available options. If an author is compiling a list of journal options for a prospective manuscript on industry-sponsored research, you can imagine how time consuming this would be. A bespoke tool with information for authors of industry-funded research and the publications professionals who assist them did not exist.

To close this gap, MPIP launched the Open Access Journal Tool for Industry (OA-JTI). This free and unique journal-finding tool is designed to allow users to quickly locate journals offering OA publishing options for manuscripts reporting on industry-sponsored studies. Within the tool, users can narrow their journal search by therapeutic area, publisher, and/or copyright license. Notably, the tool indicates whether a journal offers Gold OA for industry-sponsored research.

The OA-JTI currently includes information from over 300 journals in more than 30 therapeutic areas. Future updates will include additional journals and therapeutic areas to meet the diverse needs of authors and publications professionals who are seeking information on options for OA publishing.

Sponsor policy makers may also find the OA-JTI useful. When considering greater advocacy for OA, sponsors lacked key data, including knowledge of whether journal options would be limited if they pushed for increased use of OA options for publishing their company-sponsored research.

In addition to the OA-JTI, OA initiatives recently launched by MPIP include

Open Access Resources

Webinars

Open Access and Medical Publishing Webinar

(in collaboration with Open Pharma and ISMPP University)

Aimed at publications professionals, this webinar helps viewers understand key elements of OA options and policies as well as perspectives of key stakeholders.

Open Access—A Primer for Medical Writers Webinar

(in collaboration with AMWA)

Aimed at medical writers of all experience levels, this webinar explains the different OA models and licenses.

Access the recording on the AMWA Online Learning site (complimentary for AMWA members only)

Open Access Blog Series

Chris Winchester, CEO of Oxford PharmaGenesis, former Chair of the ISMPP Board of Trustees, and co-founder of Open Pharma, on the challenges and the importance of OA.

Martin Delahunty, former Global Director with the Open Research Group of Springer Nature, on the history of OA publishing, where the movement is headed, and the role of OA in facilitating transparency and credibility.

Paul Wicks, Vice President of Innovation at PatientsLikeMe, on the importance of providing patients and caregivers open access to the latest research results.

Although we know that these resources will not address all barriers to OA adoption by industry, we hope that the OA-JTI and the other MPIP OA initiatives will facilitate understanding of OA and advance the shared goal of increasing access to the results of industry-sponsored clinical research.

We hope that the OA-JTI and the other MPIP OA initiatives will facilitate understanding of OA and advance the shared goal of increasing access to the results of industry-sponsored clinical research

June 14, 2019

Author Insights

Author Insights On: Transparency and Credibility of Industry-Sponsored Clinical Trial Publications: A Survey of Journal Editors

Why conduct a survey about transparency and credibility?

Over the past decade, we have seen an increasing demand for greater transparency in industry-sponsored research and the negative impact a lack of transparency can have on trust and credibility of published results. At the same time, we have also been encouraged by a continuous wave of positive change in medical publication practice aimed at increasing transparency and credibility. Best publication practices now include trial registration, acknowledgement of funding and editorial support, inclusion of trial identifiers, and adherence to tighter authorship guidance shaped by recommendations from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and Good Publication Practice.

Read the full articlehere

In my experience, most people, no matter their line of work, agree that transparency improves the accuracy and objectivity of data interpretation. Both MPIP and many sponsors of industry research have made tangible efforts toward improving and implementing best publications practices. We at MPIP were curious whether medical journal editors were observing any improvements that might be related to these efforts.

Both MPIP and many sponsors of industry research have made tangible efforts toward improving and implementing best publications practices.We at MPIP were curious whether medical journal editors were observing any improvements that might be related to these efforts.

Why are medical journal editors’ perceptions important?

Medical journal editors are critical gatekeepers in the publishing model; they review and weed out submissions of inferior quality, and they validate the utility and integrity of the science published in their journals.

What did medical journal editors say about transparency and credibility of industry-sponsored publications?

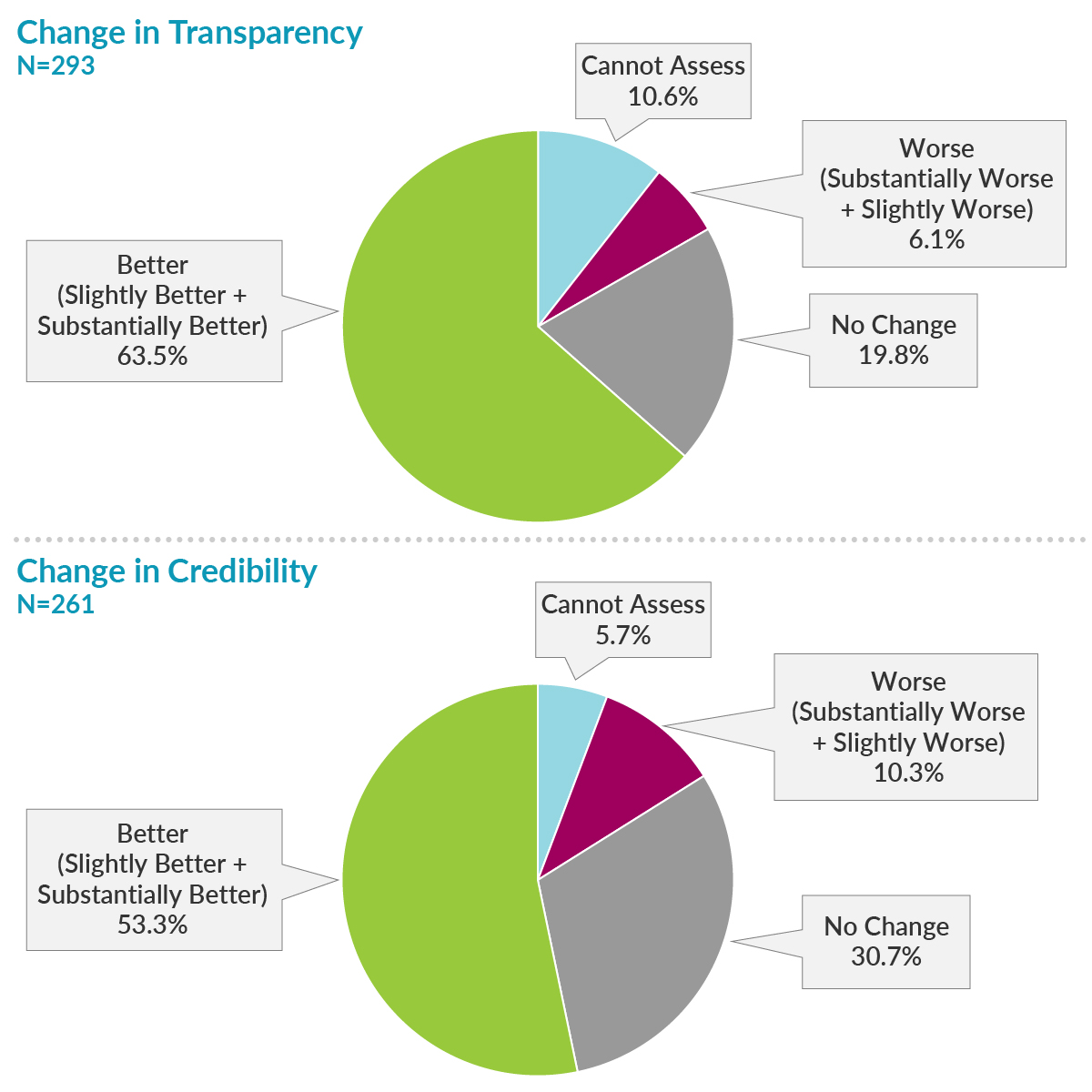

Of 6,013 editors from 885 journals who were sent the survey, 510 opened it and took action by completing at least a portion of the survey, 293 completed the first primary endpoint question on transparency, and 261 completed the primary endpoint question on credibility. Most respondents reported improvements in transparency and credibility, while only a small portion of respondents reported worsening of transparency and credibility.

What recommendations for improving credibility were most relevant?

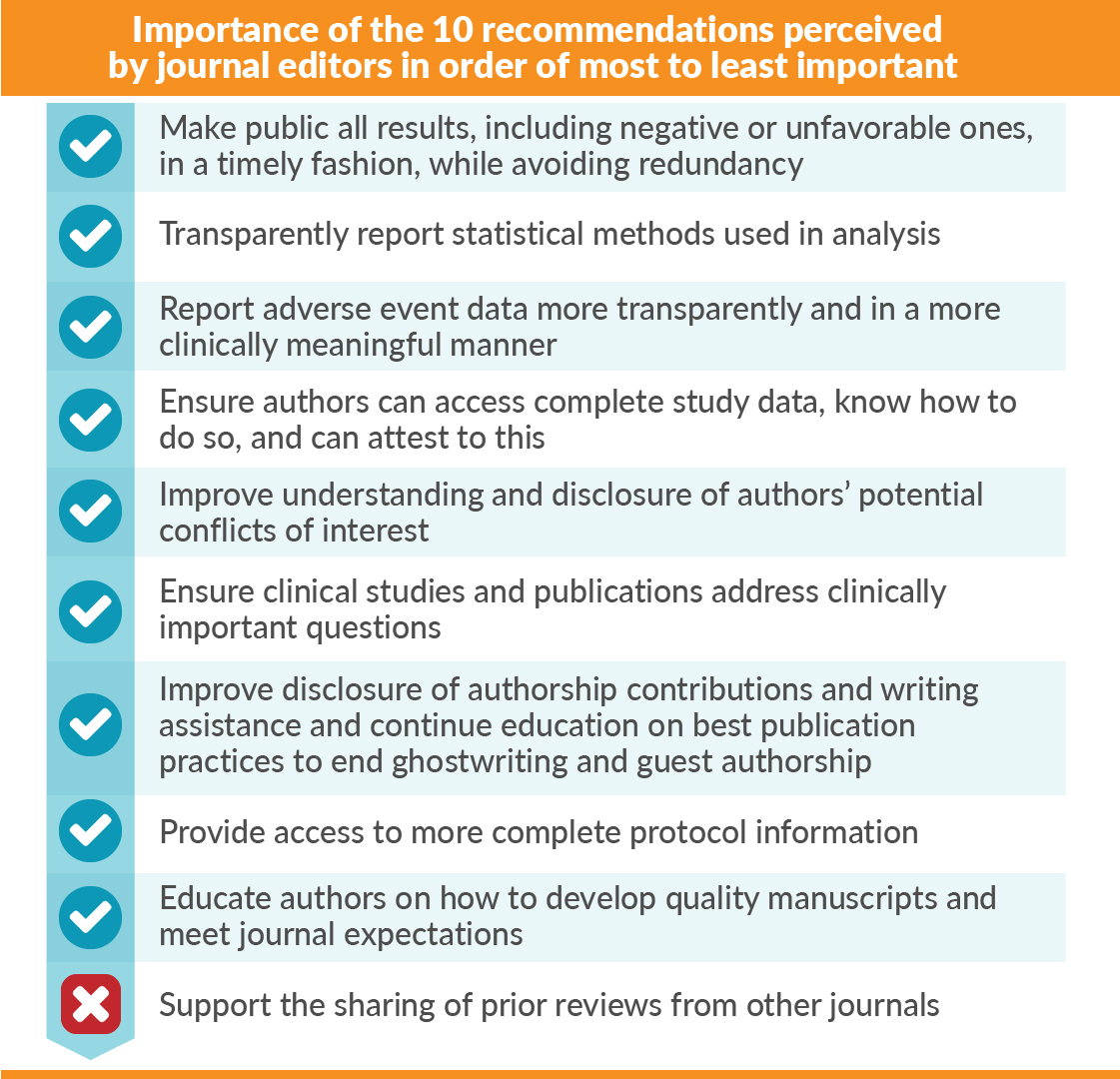

We asked the editors to rate the importance and adoption of 10 recommendations previously defined at an MPIP Roundtable of pharmaceutical company representatives and journal editors.1 Responding editors perceived 9 of 10 of the recommendations to be moderate to extremely important (![]() ). Only the “sharing of prior peer-reviewers’ comments” was considered minimally important (

). Only the “sharing of prior peer-reviewers’ comments” was considered minimally important (![]() ). However, the editors perceived only a minimal to moderate level of adoption of the 10 recommendations, with “sharing of prior reviews” as the least adopted.

). However, the editors perceived only a minimal to moderate level of adoption of the 10 recommendations, with “sharing of prior reviews” as the least adopted.

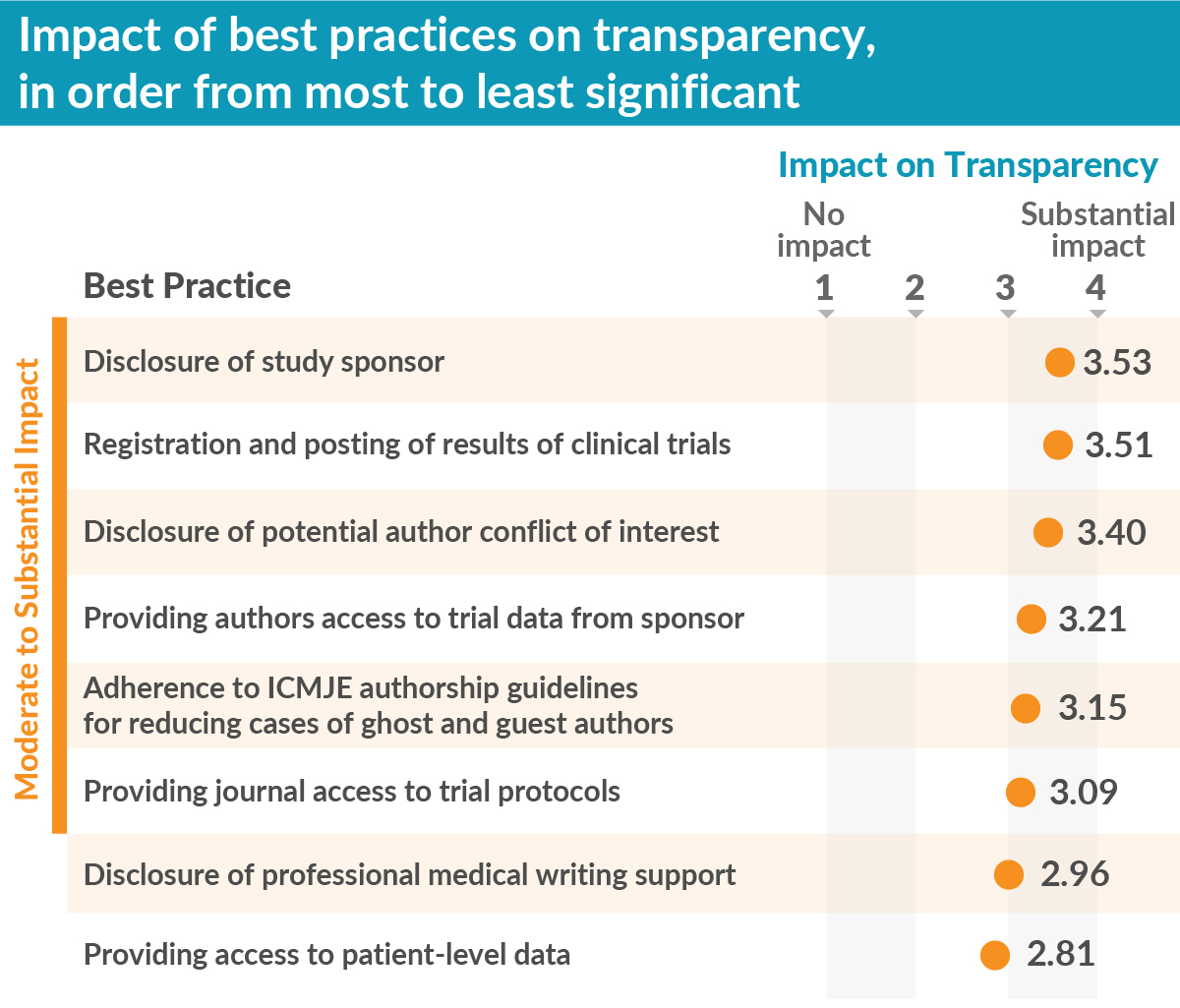

We also tested eight well-known publication best practices to assess how each contributed to improving transparency. We found the best practices “disclosure of the study sponsor” and “registration and posting of trial results” were the most impactful. Further, six of the eight best practices had moderate to substantial impact on transparency, thereby supporting the importance of efforts, from MPIP and other stakeholders, to encourage uptake of best practices.

What does this mean for MPIP and industry-sponsored publications?

Our survey results indicate that some of the transparency efforts are paying off. It is unclear whether the lower adoption ratings for the 10 recommendations was the result of a true lack of adoption or if efforts made by the pharmaceutical industry were poorly communicated.

Credibility, which was also surveyed, is a more complex concept that encompasses transparency and other factors. The perceived improvement in credibility was 10% lower than the perceived improvement in transparency. It is conceivable that credibility may require more time to show progress.

Nevertheless, these results are encouraging and consistent with other independent reports and industry scorecards that demonstrate enhancement in transparency in recent years.2-4Although our respondent population was of reasonable size (293), our low response rate discourages generalization of these results to all medical journal editors. Nevertheless, these results are encouraging and consistent with other independent reports and industry scorecards that demonstrate enhancement in transparency in recent years.2-4

Going forward, MPIP will continue to support the adoption and embedding of best practices within medical publications, in particular within the pharmaceutical industry, as well as improved communication of these efforts to journal editors and other stakeholders.

Author note: The opinions expressed here are my own and not those of my employer.

References

- Mansi BA, Clark J, David FS, et al. Ten recommendations for closing the credibility gap in reporting industry-sponsored clinical research: A joint journal and pharmaceutical industry perspective. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2012;87(5):424-429.

- Gopal AD, Wallach JD, Aminawung JA, et al. Adherence to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ (ICMJE) prospective registration policy and implications for outcome integrity: a cross-sectional analysis of trials published in high-impact specialty society journals. Trials. 2018;19(1):448.

- Miller JE, Korn D, Ross JS. Clinical trial registration, reporting, publication and FDAAA compliance: a cross-sectional analysis and ranking of new drugs approved by the FDA in 2012. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009758.

- Miller JE, Wilenzick M, Ritcey N, et al. Measuring clinical trial transparency: an empirical analysis of newly approved drugs and large pharmaceutical companies. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017917.

January 31, 2019

Open Access

Open Access Is Needed to Maximize Transparency of Industry-Funded Research

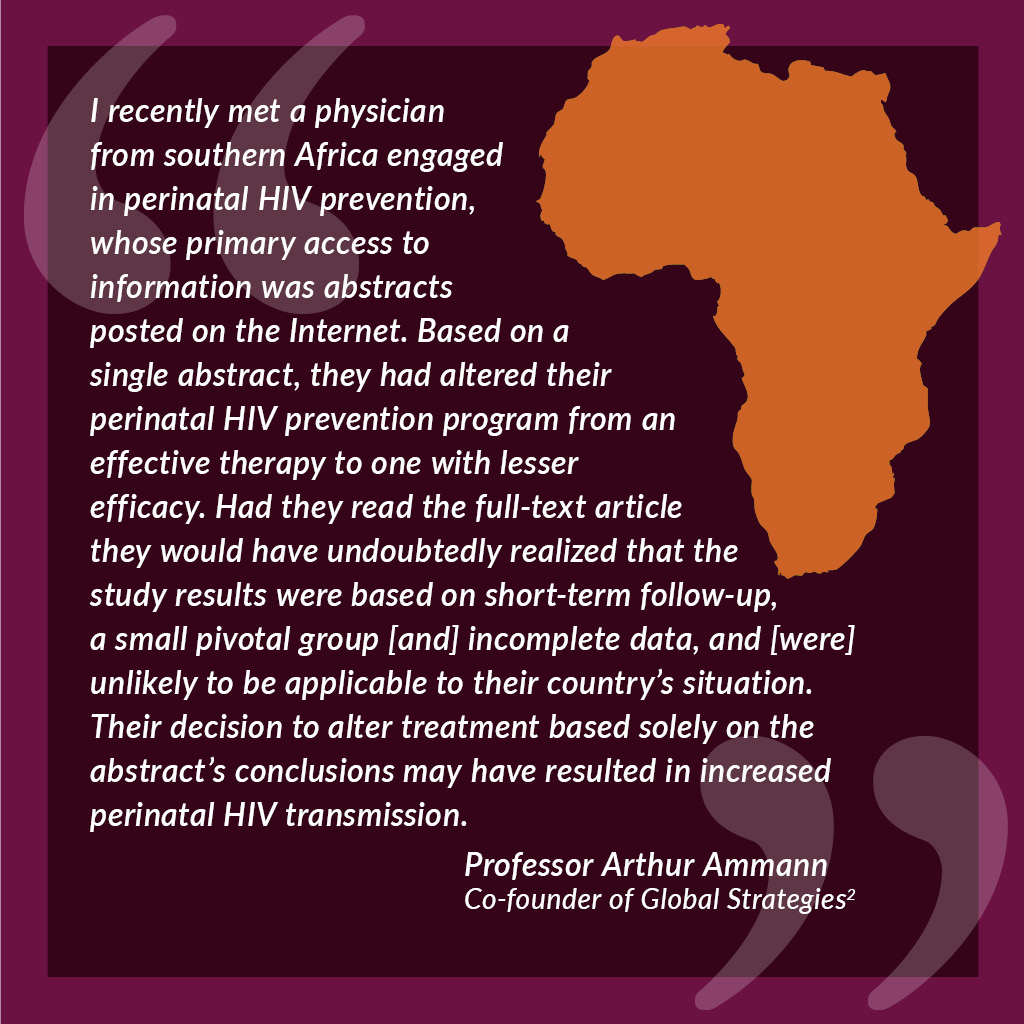

The arguments in favor of open access, in terms of unrestricted and equitable access to the results of medical research, are widely aired.1 However, sometimes personal stories have the biggest impact and, for me, the true importance of open access was brought home by Professor Arthur Ammann, Co-founder of Global Strategies for HIV Prevention.

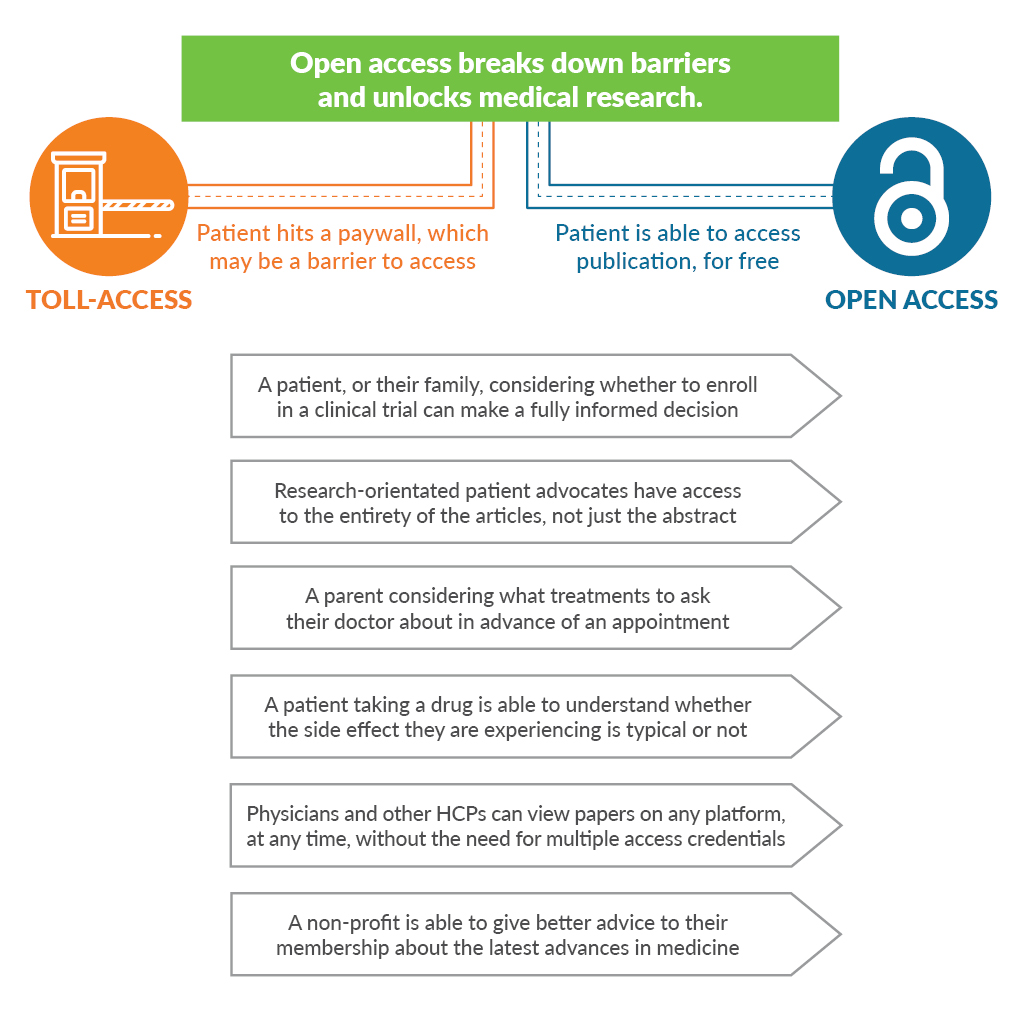

Professor Ammann’s story shows how creating an accessible abstract while restricting access to the full article has the potential to create serious issues for doctors and patients. Although abstracts easily disclose the efficacy benefits of clinical trials, the safety concerns and limitations of a study can often be found only in the main body of a research article. When an article is published in a subscription journal, this information lies behind a paywall, and the non-subscriber reading the abstract alone may be unable to make a fair and balanced assessment of a new treatment. As healthcare communicators, we have a duty to ensure the transparent and effective reporting of clinical data. I find myself asking why we are not doing more to ensure that all the relevant information in a research article is available to everyone who needs it.

To answer this question, we need to take a look at the history books. Learned journals have changed little since their beginnings 350 years ago at the dawn of the Enlightenment. Although most journals remain reliant on subscriptions for a key part of their revenue, some have diversified their revenues through advertising, copyright permissions, and, more recently, article-processing charges (APCs). First introduced by open access journals, APCs have now been adopted by hybrid journals, which offer authors and research funders the option to publish in a subscription journal without the article being restricted by the journal’s paywall. Most governmental and charitable research funders now require authors to publish the research they fund open access, in open access or hybrid journals to ensure public access to research conducted for public benefit.3 Some funders are going further. To address concerns that hybrid journals, which have both APCs and subscription charges, are “double dipping,” research funders behind Plan S are seeking to ensure immediate open access to all articles arising from research they fund, without the payment of APCs to journals that also charge a subscription.4

I find myself asking why we are not doing more to ensure that all the relevant information in a research article is available to everyone who needs it.What does this all mean to us in the pharmaceutical industry? At the inaugural meeting of Open Pharma at the Wellcome Trust in January 2017,5 we brought together a diverse mix of stakeholders to see what role our industry should play in helping to advance the publication of science. The participants gave us a clear message: as the pharmaceutical industry funds up to half of all medical research, it should join other research funders in requiring that the research it funds be published open access. Shire became the first pharmaceutical company to introduce a mandatory open access policy, in January 2018,6,7 with others interested in following their lead.

By mandating open access for all articles, pharmaceutical companies can proactively avoid criticism, such as that they only pay for open access for studies with positive results.I firmly believe that open access is the future for publishing industry-funded research. Many pharmaceutical companies already encourage the research they fund to be published open access whenever journals allow. So, what is the added value of mandating open access for all articles reporting research? Open access increases discoverability of research articles, for example by allowing researchers to find clinical trial registration numbers that are only given in the full text. Open access also allows readers complete access to the entire publication, including strengths and limitations, detailed safety data, funding sources, and author disclosures, as discussed above. By increasing accessibility, open access also appears to increase impact, whether measured in terms of citations or online/social media attention.1 By mandating open access for all articles, pharmaceutical companies can proactively avoid criticism, such as that they only pay for open access for studies with positive results.

Of course, anyone advocating for change should pay attention to the law of unintended consequences. My biggest concern is that drastic changes in publishing may damage the scholarly publishing ecosystem. In a world of declining trust in authority, reputable journals with high-quality peer review processes are more important than ever. Yet, despite the uncertainty surrounding open access publishing, simply doing nothing may pose the biggest risk of all. As other research funders mandate open access, industry is being left behind. None of us wants to see a world in which medical research is published in different journals governed by different rules depending on whether it had industry or non-industry funders.

Working together, we can maximize the disclosure of industry-funded research while maintaining the healthy scholarly publishing ecosystem on which such disclosure depends.I believe that the transition to open access is inevitable. To maximize the benefits of this transition while managing the risks, we need to see increased communication between stakeholders working in forums such as Medical Publishing Insights & Practices (MPIP), International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP), and Open Pharma. Working together, we can maximize the disclosure of industry-funded research while maintaining the healthy scholarly publishing ecosystem on which such disclosure depends.

To learn more about open access, take a look at the excellent MPIP Open Access Reference Site and, to stay up-to-date with recent developments, subscribe to the Open Pharma blog.

References

- Tennant JP, Waldner F, Jacques DC, et al. The academic, economic and societal impacts of open access: an evidence-based review. F1000Res. 2016;5:632.

- The PLoS Medicine Editors. The impact of open access upon public health. PLoS Med. 2006;3(5):e252.

- Larivière V, Sugimoto CR. Do authors comply when funders enforce open access to research? Nature. 2018;562(7728):483-486.

- cOAlition S - Making full and immediate Open Access a reality. Science Europe. https://www.coalition-s.org/feedback/. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- Winchester C. Embracing change in medical publishing: The Open Pharma Project. The MAP Newsletter. https://ismpp-newsletter.com. October 30, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2018.

- Shire continues to uphold high standards of ethics and transparency with adoption of open access policy for publication of Shire-supported research [press release]. Cambridge, MA: Shire; January 23, 2018. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- Shire announces new open access policy. The MAP Newsletter. https://ismpp-newsletter.com. January 30, 2018. Accessed December 14, 2018.

November 19, 2018

Open Access

Open Access: What Transparency Means to Me

At the turn of the new millennium, the open access publishing model was in its infancy, considered to be experimental, and led with evangelical zeal by a few, but vocal, individuals.1 It was also perceived as “anti-publisher”—perhaps understandably, as the incumbent scientific, technology, and medical journal publishers, chained to the shackles of their subscription model, reacted defensively.2 Despite this, we witnessed the rise of new, innovative, borne-open access publishers, such as BioMedCentral (BMC) and Public Library of Science (PLOS). Free from the restraints of a subscription model, they blazed a trail for others to follow. Pharmaceutical and medical publication professionals also viewed open access sceptically, considering it as “pay to publish” or just plain “vanity publishing.”3 A growing number of advocates, however, began to promote open access as a means of supporting greater transparency in data reporting and demonstrating how it could be essential to patient care, scientific understanding, and credibility.

In 2008, I joined Nature Publishing Group (NPG) to find myself at the leading edge of a new movement within traditional subscription-based publishing towards an open access model. Refreshingly, the emphasis was on building a positive view of open access, rather than reacting to it as a threat; we felt that it represented a major opportunity and benefit to the wider scientific community.

The following year, NPG significantly expanded its open access author choices,4 through both “green” (self-archiving) and “gold” (author-pays) publication routes. Then, Nature Communications was announced as the first Nature-branded online-only journal with an open access option. Buoyed by a new confidence, my team launched 11 new fully open access journals over a period of 4 years. Overall, much was made of author choice and being cognizant of the increasing open access mandates of research funders such as the Wellcome Trust.

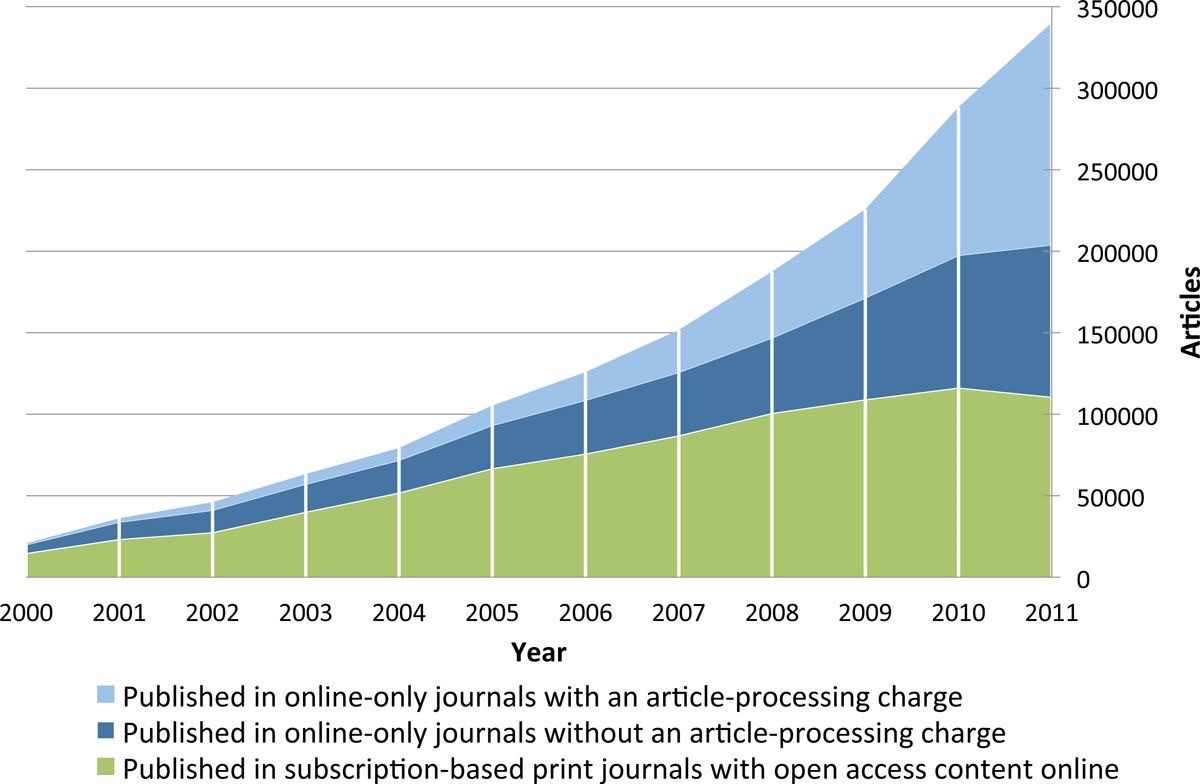

In 2011, I was the first academic publisher to give a keynote presentation5 at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) in Washington DC. I seized upon this opportunity to promote the benefits of open access and digital innovations enabled by the World Wide Web. To add weight to the open access argument, we needed credible evidence-based studies and proofs of concept. In 2012, a pivotal research paper by Mikael Laakso and Bo-Christer Björk found that the prevalence and effectiveness of open access was increasing (Figure 1).6 The authors concluded that “It no longer seems to be a question whether open access is a viable alternative to the traditional subscription model for scholarly journal publishing; the question is rather when open access publishing will become the mainstream model.”

Figure 1. Annual volumes of articles in full immediate open access journals, split by type of open access journal. Laakso M and Björk BC. BMC Medicine. 2012;10:124.6

The pace of open access development at NPG did not relent. In 2014, the Nature Partner Journals were announced7 as a new series of online open access journals, published in collaboration with world-renowned international partners, including The Scripps Research Translational Institute and NASA. The next year, Springer and Nature merged to bring BioMedCentral into the fold.

More recently, a pivotal moment for open access in clinical trials publishing, led by Oxford Pharmagenesis, was the launch of the Open Pharma8 initiative. This is a joint initiative of forward-thinking pharmaceutical clients, publishers, patients, academics, regulators, editors, non-pharmaceutical funders, and societies to identify the changes needed for wider open-access adoption and how that might be achieved.

On the back end of this initiative, and in a drive towards greater transparency, Shire Pharmaceuticals9 announced at the 2018 European Meeting of ISMPP that it would implement a policy whereby results of Shire-sponsored studies would only be submitted to journals that provided open access to the full text. Shire’s focus on rare diseases was a key factor behind the decision, as transparency is particularly important when it comes to advancing new therapies for treating the 7,000 or so identified rare diseases that still, in most cases, have no treatment options. Shire’s move will hopefully provide the impetus for other pharmaceutical companies to follow suit.

So, looking back on the last 10 years, the open access landscape has dramatically changed and for the greater good. A new generation of millennial clinical and scientific researchers have now fully embraced open access and regard the subscription-based, firewalled publishing model as a huge anachronism. Hopefully, within the pharmaceutical industry, threat has been superseded by opportunity to serve the greater good of scientific and healthcare advancement.

Over the next 10 years, I foresee an even more rapid advancement of open access and data transparency supported by new technologies, particularly artificial intelligence and machine learning. Keep a close eye, because things will move quickly to enable greater transparency, accountability, and efficiencies.

References

- Harnad S. Open Access: "Plan S" Needs to Drop "Option B." Open Access Archivangelism. http://openaccess.eprints.org/. September 14, 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

- Willinsky J. The publishers’ pushback against NIH’s public access and scholarly publishing sustainability. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(1):e30.

- Davis P. Open access and vanity publishing. The Scholarly Kitchen. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/. October 21, 2009. Accessed November 7, 2018.

- Expanded green and gold routes to open access at Nature Publishing Group [press release]. London, UK: Nature Publishing Group; January 22, 2009. Accessed November 7, 2018.

- Delahunty M. Future trends in maximizing impact of medical publications. Keynote presentation at: International Society for Medical Publication Professionals 7th Annual Meeting; April 4-6, 2011; Arlington, VA. Accessed November 7, 2018.

- Laasko M, Björk BC. Anatomy of open access publishing: a study of longitudinal development and internal structure. BMC Med. 2012;10:124.

- Nature Partner Journals, a new brand of open access journals [press release]. London, UK: Nature Publishing Group; April 2, 2014. Accessed November 7, 2018.

- Winchester C. Embracing change in medical publishing: The Open Pharma Project. The MAP Newsletter. https://ismpp-newsletter.com. October 30, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2018.

- Shire continues to uphold high standards of ethics and transparency with adoption of open access policy for publication of Shire-supported research [press release]. Cambridge, MA: Shire; January 23, 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

October 23, 2018

Open Access

Calling Time on Toll-Access Publishing

Not long ago, we called the people taking part in clinical trials “subjects.” Only recently have we begun to change our language and attitude and started to treat the people who volunteer their time and risk their health to support scientific research as true participants.

These changes are happening because people living with illness (including patients, parents, and caregivers) are increasingly being invited to participate in and make decisions in scientific grant committees, FDA advocacy panels, medical conferences, journal peer review, protocol design, and even co-producing research1. But whether wittingly or not, we are still blocking patients and caregivers from becoming better informed when we publish our research behind paywalls.

As an industry, we need to stop. And if you’re reading this, you are the best placed person to make that happen.

Why do we need better informed and educated patients? Aside from the fact that better informed and educated patients achieve better outcomes2, patient involvement in research has been particularly beneficial in clinical trial design, wherein one analysis of financial value suggested a 500-fold return on investment, equivalent to accelerating a pre-phase 2 product launch by 2.5 years3. Given all that, it remains perplexing that when an innovative life sciences company invests billions of dollars into research, the vast majority of outputs into the peer-reviewed literature demand “toll access.” That means an activated and engaged patient or caregiver trying to delve into a company’s scientific outputs is asked to pay around $35-$50 for the privilege of reading or even just “renting” an article that could better inform or allow them to take actions that would help the company achieve their goals.

Say you were the parent of a child living with multiple sclerosis. An impressive industry-sponsored study was recently published comparing 2 drugs for children living with multiple sclerosis in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, featuring 215 participants from 87 centers in 26 countries over the course of 3 years. Would you like to read it? For $20 you can rent it for 24 hours. Readers will know better than I just how much such a study must have cost its sponsors. Asking some of the most interested yet most vulnerable people to shoulder the burden seems galling.

Although the cost of an individual article may seem low, for many people with a chronic illness, the financial impact of living with the disease is itself a hardship4. While we don’t know how many patients simply give up when they hit a paywall, we can see that patient-orientated open access articles in otherwise closed-access journals often receive many times more views. “ALS Untangled” is an open-access series in the subscription-based journal Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration. Articles in this series regularly receive between 2,000-20,000 views in contrast to only a few dozen or hundreds of views for articles behind the paywall.

It’s not just patients, but also front-line clinicians, allied health professionals, researchers, journalists, and people working for non-profits who may not be able to read, cite, and build upon these hard-fought research outputs. Even well-resourced universities have had to tighten their libraries’ budgets and stop paying for expensive journal subscriptions. Many journals now offer a range of open-access options, and article publishing fees are around $2,000-$3,000 per article, breaking down the unnecessary toll booth, providing a sustainable business model for publishers, and increasing the free flow of high-quality information.

Angry yet? You should be! What were the last few trials that everyone at your company really celebrated? Busy doctors and their patients are often attempting to access the results of these studies on personal smartphones as they run between meetings and appointments. Try to access the full text of the article reporting the results on a personal smartphone or computer, off your company’s network. Could you read it in one click? 10? Did you need to register? Pay money? Was it so frustrating that you gave up? Welcome to the patients’ world.

Make it your mission and ensure that you and your company become advocates for the value of open access to patients and healthcare professionals.

References

- Wicks P, Richards T, Denegri S, Godlee F. Patients’ roles and rights in research. BMJ. 2018;362:k3193.

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self‐management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2017;42(4)1443–1463. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00669.x

- Levitan B, Getz K, Eisenstein E, et al. Assessing the financial value of patient engagement: a quantitative approach from CTTI’s Patient Groups and Clinical Trials Project. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2018;52(2):220-229. http://doi.org/10.1177/2168479017716715

- Jaspers L, Colpani, V, Chaker L, et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(3):163-188. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9983-3

October 22, 2018

Open Access

MPIP Launches Open Access Initiatives

Growing advocacy for transparency and access to results of clinical trials has prompted considerable debate on the topic of open access publishing and highlighted a lack of common understanding of what open access is, why it is important, and how it works. Consistent with our goal of promoting greater transparency in industry-sponsored publications, MPIP has developed an Open Access Reference Site and blog series to raise awareness of open access, including its importance in meeting shared transparency goals. The Open Access Reference Site includes answers to frequently asked questions on open access publishing, and our blog series will feature expert insights on open access.

July 20, 2018

Future Perspectives in Peer Review

The Paradoxical Evolution of Peer Review

Paradoxically, peer review, which is at the heart of science, is largely a faith‑based rather than evidence‑based activity. Peer review had been studied hardly at all until the late 1980s when the International Congress on Peer Review and Scientific Publication, a conference held every 4 years, began. Research shows that peer review is slow, expensive, somewhat of a lottery, poor at detecting errors, prone to bias, and easily abused. Highly original science is often rejected by peer review, leading some to consider the process as anti-innovatory and conservative.

Extensive examination of the existing research in the form of 2 systematic Cochrane reviews1,2 did not find peer review to be effective, although we must remember that absence of evidence of effectiveness is not the same as evidence of ineffectiveness. Despite the evidence and challenges, peer review of manuscripts continues on a massive scale, consuming a large amount of resources.

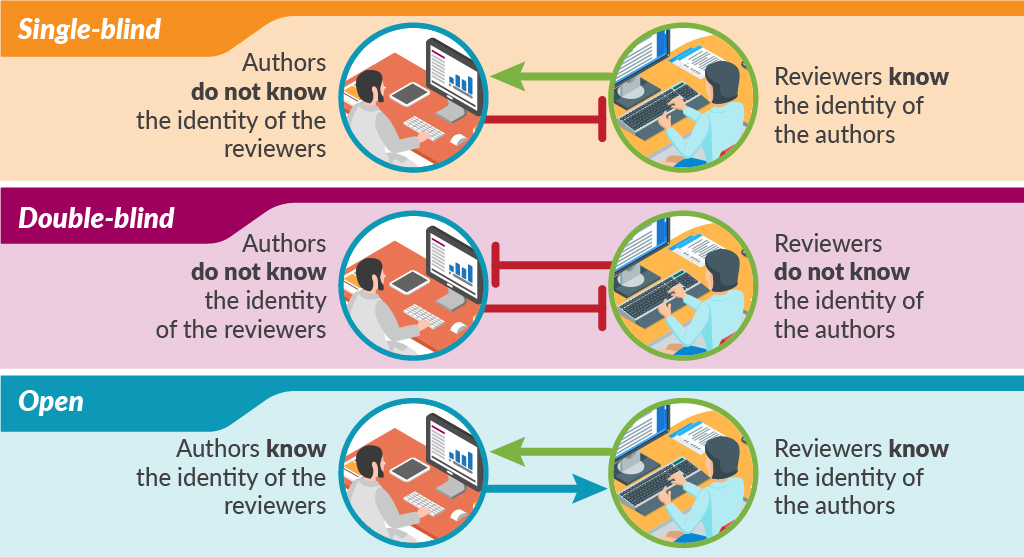

Traditional peer review is single-blind in that the authors do not know the identity of the reviewers but the reviewers know the identity of the authors. This model probably still accounts for most peer review, although the number and nature of the reviewers varies considerably. There is also considerable variation in how much the reviewers contribute to the final decision on publication.

In double-blind peer review, the reviewers are also blinded to the identity of authors. Large-scale trials of this double-blind of peer review failed to show the benefit of this practice and were followed by steadily opening up the peer-review process.

Some methods of open peer review allow authors to see the reviewers’ names and comments, while other methods publish all the comments along with the paper. The most open of peer-review models conducts the whole process online, in full view of the readership.

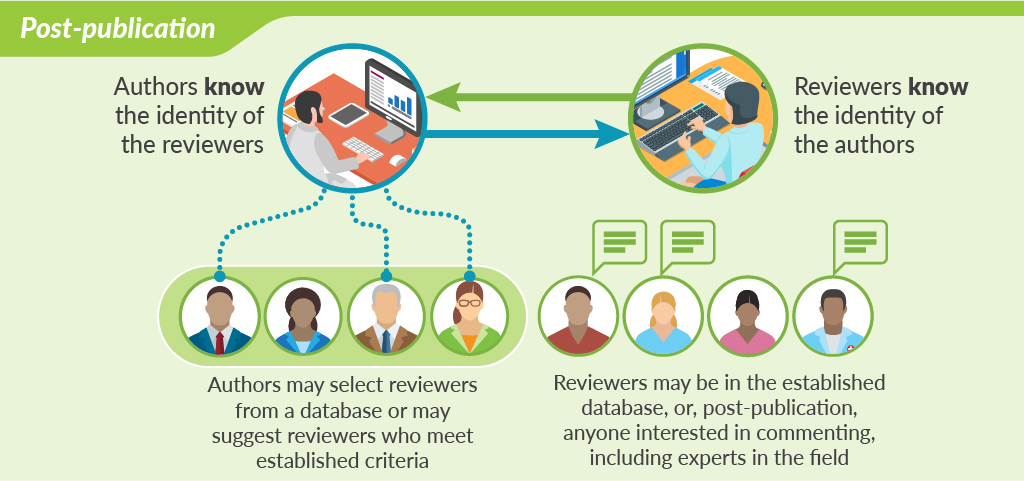

Perhaps the most cutting-edge innovation in peer review is open peer review that takes place after publication. This model of peer review is shown by F1000Research and accompanying “journals” like Wellcome Open Research and Gates Open Research. After a preliminary check of the studies, including ethics committee approval and confirming compliance with standard publication guidelines, the papers are published online together with all the raw data. Peer review takes place after this online publication. The authors select reviewers from a database or may suggest their own reviewers based on established criteria—such as being academics of certain standing (ie, full professor). Reviewers are asked to comment not on the originality or importance of the study, but simply on its methodologic soundness and whether the conclusions are supported by the methods and data. Once the reviews are posted, authors and readers can see both the reviews of the published paper and the identities of the reviewers. After publication, anybody can post comments at any time. Authors have the opportunity to respond to reviewers’ comments or point out where reviewers have misunderstood the study. Peer review becomes less of a one-time judgement and more of an ongoing dialogue aimed at ensuring the best possible paper is published.

While there are many innovations in how the peer review is conducted, sadly, there doesn’t appear to have been a rigorous evaluation of the effectiveness of these innovations. Nevertheless, peer review is evolving: the process is opening up, full data sets are being included, and authors are expected to declare their contributions and conflicts of interest. Generally, there is more interest in the science of science publishing.

References

- Jefferson T, Alderson P, Wager E, Davidoff F. Effects of editorial peer review: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287(21):2784-2786. doi:10.1001/jama.287.21.2784.

- Wager E, Middleton P. Effects of technical editing in biomedical journals: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287(21):2821-2824. doi:10.1001/jama.287.21.2821.

Supplemental Reading List

Smith R. Classical peer review: an empty gun. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(suppl 4):S13. doi: 10.1186/bcr2742.

Spicer A, Roulet T. Explainer: what is peer review? The Conversation.http://theconversation.com/explainer-what-is-peer-review-27797. Published June 18, 2014. Accessed July 16, 2018.

May 9, 2018

Perspectives on Predatory Journals and Congresses

Open Access or Public Trust: A False Dichotomy

Although the term ‘predatory publishing’ wasn’t coined until Jeffrey Beall notoriously introduced it in 2011, the notion that open access (OA) was undercutting or even corrupting the quality of scholarly publishing goes back to at least 2007 with a campaign led by Eric Dezenhall on behalf of some large commercial subscription publishers. The result was the ‘Partnership for Research Integrity in Science and Medicine’—PRISM—which set out to question the quality of articles being made freely available and to push back on the first stirrings of public and OA mandates by funders. At the time, I had been a professional editor for 9 years, in sole charge of an Elsevier journal before moving to PLOS to help launch and run some of their OA journals. Despite changing business models, there was no difference in the rigour with which I conducted peer review. Fortunately PRISM backfired and sank without trace, but the myth that OA somehow meant predatory, and either low quality or no peer review, has stubbornly and erroneously persisted.

This is not to say that fraudulent practices do not exist—they do and should be taken seriously—but they are not unique to OA journals and they should not be seen as a product of the model. The vast majority of OA journals and articles are rigorously peer reviewed and hosted by publishers and editors who genuinely care about the integrity of science. As pointed out by Angela Sykes in a previous post in this series, the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) has stringent criteria for a journal to be eligible on their list. There is also a set of principles, created through a partnership of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (OASPA), the DOAJ, and the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME), that publishers wishing to join these organisations must adhere to.

For several years I was chair of the OASPA membership committee. Many of the applications came from independent scholars from all over the world trying to set up reputable journals in their field. What they lacked, as researchers, was training on how to go about it—an understanding of what running peer review actually entailed, the checks required before peer review can even start, and the licensing, copyright, infrastructure, and metadata required to make content discoverable (the need for DOIs, for example). It was incredibly rare to receive an application that was not genuine. Much of the work of the committee was, and remains, about education.

All publishers have a responsibility to provide a high-quality rigorous service for their authors, editors, reviewers, and readers. There is no doubt that there are problems and corrupt practice in journal publishing, and researchers need to be confident in the credibility of a journal and publisher before they submit. We need, however, to get away from the idea that there is a dichotomy between good and evil in scholarly publishing, that there is either predatory or good practice—and that OA equates with the former. Indeed, a study by Olivarez et al. this year showed that when three researchers tried to independently apply Beall’s criteria to a number of journals, they found that not only could they not identify the same journals as each other, but that their lists included many traditional ‘top-tier’ journals.

In our digital age, the meaning of quality is changing. OA and the increasing focus on transparency, collaboration, trust, and discoverability in open science means that journals, publishers, and indeed all stakeholders involved in scholarly communication need to up their game. Peer review itself is no guarantee of quality, as the increasing number of retractions because of fraud can attest to, including from very high-profile, reputable traditional journals.

The greatest challenge is not ‘predatory’ publishers, it is the culture in which research currently operates and the focus on the journal as a proxy of researcher quality. What quality means depends on context and who is doing the evaluating. Moreover, we need to value and evaluate all the varied contributions that researchers provide to science (including their contributions to peer review) and to the wider knowledge system. Publishers, institutions, and other stakeholders can sign DORA as a commitment to this.

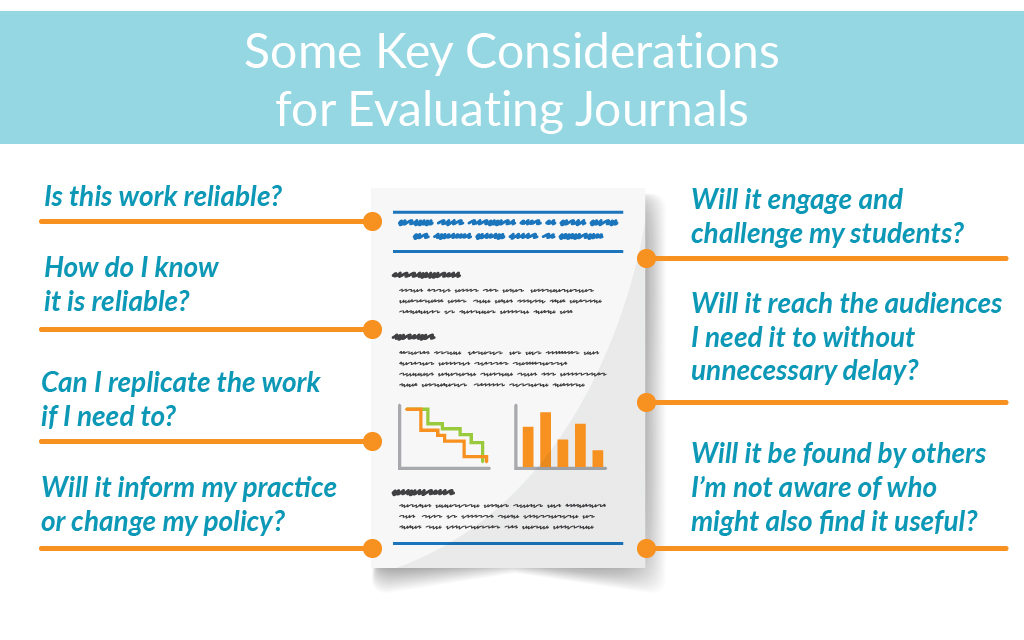

We also need to put safeguards and training in place for researchers where bad practice exists, such as the recently launched ‘Think, Check, Submit’ campaign, which aims to raise awareness among authors about what to look for in a journal before entrusting it with their work. But this applies to any journal. It is time to get away from the polarised, simplified dichotomy between predatory and good research, or subscription and OA publishing, and focus on what really counts (see Figure).

Most importantly, is it possible for others, including machines, to reuse the information so that my work can potentially contribute to the public good for the benefit of science and society?

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Helen Dodson, whose presentation at UKSG 2018 pointed me to several references and helped inform this post.

April 12, 2018

Perspectives on Predatory Journals and Congresses, Editor Interview

Insights on Predatory Journals from Patricia “Patty” Baskin

To complement the blog series on predatory journals and congresses, MPIP caught up with Patty Baskin to gain her expert insights on threats posed by predatory journals and what authors and publication professionals can do to protect their work. Patty Baskin is the Executive Editor at the American Academy of Neurology and immediate past president of the Council of Science Editors.

Visit the MPIP YouTube Channel to view the video of the interview today!

February 28, 2018

Perspectives on Predatory Journals and Congresses, Part 2: The Biopharmaceutical Industry Perspective

Addressing the Growing Problem of Predatory Journals and Publishers

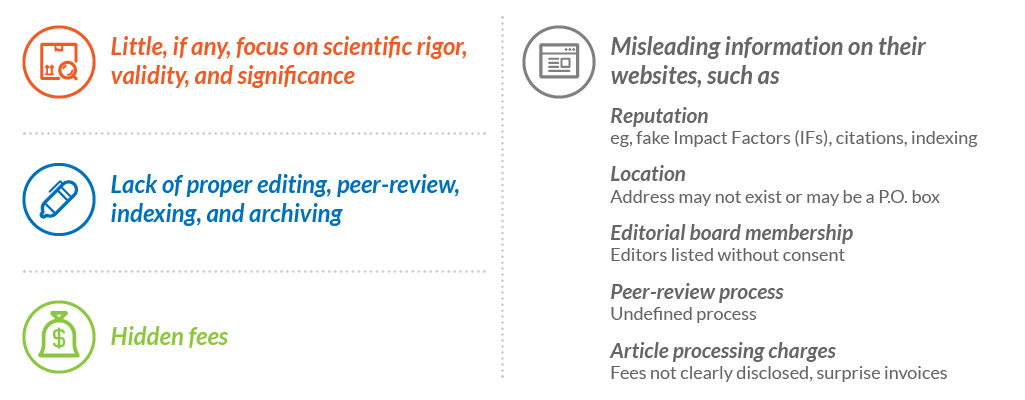

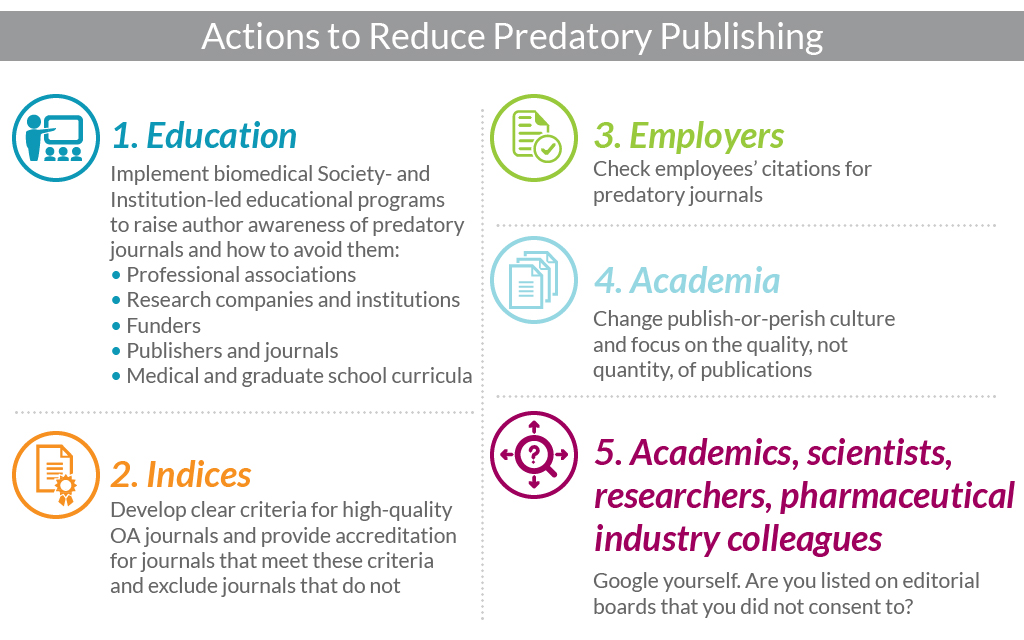

In 2008, Jeffrey Beall, an academic librarian, noticed that he was receiving spam email solicitations from broad-scoped, newly formed open access (OA) journals whose main intent seemed to be the collection of article processing/publication charges. He later coined the term “predatory” to describe these journals and publishers with dubious practices. Since then other terms have been used, such as “questionable,” “deceptive,” and “pseudo.” However, regardless of what term is used, the practices of these journals and publishers are strikingly similar. (See graphic)

Predatory publishers are a threat to scientific integrity as they make it difficult to demarcate sound science from fake science that can be damaging to public health.

In 2016 the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a complaint against OMICS, a publisher of hundreds of online journals, accusing them of deceptive practices including publishing articles with little to no peer-review and listing prominent academics as editorial board members without their consent. Then, in 2017, an article published in Bloomberg Businessweek reported that several prominent pharmaceutical companies, including AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Novartis, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer, had published in OMICS journals or participated in OMICS congresses. The article questioned “whether drugmakers are purposely ignoring what they know of OMICS’s reputation or are genuinely confused amid the profusion of noncredible journals.”

This article brought the problem of predatory journals and publishers to the forefront at Pfizer and increased our awareness of this growing problem. Since then we have taken steps to address this issue by increasing colleagues’ awareness of predatory journals, publishers, and congresses, and making changes to our publications software application such that it is easier to identify OMICS journals before they are imported into the system. We are also researching subscription-based tools such as the Journals & Congresses database, which has stringent criteria for inclusion.

But what else can be done to reduce the amount of research published by predatory journals, not only by pharmaceutical companies but by all parties involved in the development of medical/scientific publications? (See graphic)

Some organizations have already taken action. In 2014, the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) developed more stringent criteria for indexing and required journals to reapply for inclusion and, in November 2017, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a statement requesting that NIH-funded research be submitted to reputable journals to help protect the credibility of papers arising from its research investment.

Please note that the content of this blog post was prepared by me, Angela Sykes, in my personal capacity. The opinions expressed in this presentation are my own and do not reflect the views of Pfizer.

January 25, 2018

Perspectives on Predatory Journals and Congresses, Part 1: The Agency Perspective

Eight Tips for Vetting Journal and Congress Websites

Senior Editor, Healthcare Consultancy Group

Most of us are aware of “predatory” journals and congresses that promote themselves as legitimate but practice deceptive or exploitative practices at the expense of unsuspecting authors. Many fail to deliver even the basic editorial or publishing services provided by reputable journals or the networking value provided by legitimate congresses. Beyond the implications for authors in terms of cost, credibility, and reputation of being associated with these predatory journals/congresses, they also rob the scientific community of timely access to research. So what steps can we take to protect ourselves from their predatory practices?

To provide you with a framework for making your own assessments, below are 8 criteria I use to evaluate the probable legitimacy of journals or congresses based on their websites. Try not to put too much emphasis on a single item, but if a journal/congress website falls short on more than one, you may be dealing with a predator.

1. Professional website design

Less is more! Legitimate journal/congress websites typically have a “clean” look. Conversely, predators often have a “busy” look and inconsistent font choices, poor text and photo alignment, bad line breaks, and a plethora of animations. In short, they look amateurish. Scrolling text banners at the top of the page are especially suspicious. Beware if contact information uses free email providers such as Hotmail or Gmail.

2. Proper use of English

Although small international journals/congresses can be perfectly legitimate and still have a few English-as-a-second-language grammar and usage errors, a large number of typos and grammatical errors is a clear red flag. Also, look for sections that are riddled with errors alternating with error-free sections; this may be a clue that some content was plagiarized.

3. Proportional and appropriate photos

Designers of many predatory websites seem unable to reduce photo sizes proportionally, leading to “squashed” images. Also, be suspicious of a small journal/congress with a large number of alleged editorial board or faculty members, or “rock star” names in the field. These people probably are unaware they are on the website, and their photos may have been captured from LinkedIn, Facebook, etc. Finally, are photos from a past meeting cropped tightly, in such a way that you can’t tell if there were 20 attendees or 200?

4. Functional hyperlinks

Logos of sponsoring or partnering organizations should be functional hyperlinks. Predatory websites often present a dizzying collage of nonfunctional logo images, some wildly inappropriate for the subject matter of the journal/congress.

5. Complete and logical content

Look out for that little construction worker! Legitimate websites should have complete content. For example, a journal editorial board that is “Coming Soon” or an impending congress with venue information still “Under Construction” is likely a predator. Additionally, journals or congresses with an extremely broad focus, perhaps combining medical and physical sciences, are likely predators.

6. Flexibility in travel and accommodations

Can you make your own travel arrangements if you prefer? Required use of preferred travel and accommodations vendors is a red flag for congresses. Such companies are usually owned by the sponsoring organization. Look for clear statements of all registration costs and refund policies. Look for a secure mechanism for credit/debit card payments (lock icon in the URL), and avoid sites that merely provide bank transfer information.

7. Location, location, location

A very devious tactic predatory journals and congresses often use is to craft a name very similar to that of a legitimate counterpart, or to “clone” the content of a legitimate website, or to associate their predatory journal with a legitimate one on the same site. Often they just add a word, such as “American” or “International,” to a legitimate journal/congress name. Unmasking these frauds can be very challenging.

Predators will often spoof a location in the United States or Europe, but there are web tools that can trace the true location of the web domain housing a website. You can also use Google Earth to check the street address and make sure it is not simply a house or a storefront. Be cautious if the address given is in Delaware, as incorporation laws make it easy for an overseas predator to register a business there.

8. Networking

Finally, network with your senior colleagues. Has anyone ever heard of this journal or congress? Have they published in the journal or attended a meeting? Were their experiences positive?

A little due diligence upfront will pay off in the long run to ensure you get the most from your publication and congress experiences. Although the tips I’ve provided here may give you some objective evidence regarding the legitimacy of a journal/meeting, your instincts are also valuable. If it feels wrong, it probably is.