Transparency and Data Sharing Blog

December 4, 2017

Insights on the ICMJE Data Sharing Statement, Part 4

Data Sharing to Further Science

Chair of GSK Data Disclosure Medical Governance Board

Clinical research needs volunteers to participate in studies—they participate, providing informed consent, with an understanding that the information and data generated will help further scientific knowledge and medical science, ultimately benefiting patients.

Without public disclosure of the findings in journals, at congresses, and on internet-based registers, this fundamental scientific benefit is limited. We and others have developed policies and processes to make results from our clinical trials publicly available. But is this sufficient? Journal articles provide aggregate data; they do not provide other researchers with access to the underlying patient-level data so that these data can be interrogated and used to help answer other research questions.

A number of platforms have emerged over the last 5 years through which researchers can access anonymized patient-level data. We use the Clinical Study Data Request site (www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com ), which is also used by 12 other sponsors and lists more than 3,500 studies as available for data sharing.

Researchers are provided with remote access to anonymized patient-level data in a secure access system where statistical software is provided and researchers can download results of their analyses. This system protects the data from inadvertent public disclosure and prevents use of the data for a purpose that has not been scientifically and independently reviewed or approved.

However, the secure access system is costly and can be cumbersome for researchers; there can be difficulties where researchers wish to use other statistical software or combine the data we provide with other data available outside the system or in another system. What are the alternatives?

Security of the data is a must. However, data security in terms of a secure IT system does not necessarily need to be provided by the study sponsor or data provider. Therefore, where researchers provide assurances that the data will be stored and used in a secure IT environment with data governance controls, GSK now provides encrypted data directly to researchers. We believe this approach facilitates the use of the data for science with controls to protect the data from misuse and inadvertent disclosure.

As more and more data-sharing platforms emerge, if the research community is to fully realize the scientific and patient benefits of data sharing and meet the expectations of volunteers who participate in studies, we need to move away from reliance on remote, centrally provided data access systems.

October 26, 2017

Insights on the ICMJE Data Sharing Statement, Part 3

What Transparency Means to Me, as the Founder of Bioethics International and the Good Pharma Scorecard

Assistant Professor,

New York University School of Medicine

President,

Bioethics International

As the founder of the nonprofit Bioethics International and the Good Pharma Scorecard , I have been working on developing standards for clinical trial transparency and benchmarking the performance of new drugs and drug companies against those standards. Our goal is to improve ethics, trustworthiness, and patient-centricity/engagement in the development and commercialization of medical products and healthcare innovation. Our initial area of focus is clinical trial transparency.

At BEI, transparency means that trials are registered, have summary results accurately reported in a public databank, are submitted for publication in the medical literature, and comply with US disclosure requirements defined in the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA). We also support the sharing of patient-level data and the returning of lay summary results to trial participants.

In the Good Pharma Scorecard, we assess transparency for 3 different groups of trials: all trials in an FDA-approved New Drug Application (NDA), patient trials (trials conducted in patients, excluding trials in healthy volunteers), and FDAAA-applicable trials (trials legally required to be reported in ClinicalTrials.gov).1

We benchmark transparency using these 3 different sets of trials, because we found that clinical trial transparency means different things to different people, groups, and institutions. Thus, we try to provide key stakeholders with the performance metrics that are meaningful and useful to them.

We regularly convene stakeholders such as patient groups, physician groups, ethicists, academics, and companies to understand what clinical trial transparency and ethical innovation means to them. In turn, we help catalyze stronger consensus and operationalization of best practices. We also try to connect with regulators and other groups to develop guidance and opportunities to align our work with theirs.

As part of this work, my team at BEI reviewed the data sharing statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), which advises researchers to publicize their data-sharing policy each time they publish clinical trial results in one of their member journals. We applaud this step forward, but the ICMJE was largely silent on the contents of those policies. Technically, an author could have a policy that states they won’t share any data.

To avoid this, BEI proposes researchers and trial sponsors commit to sharing analyzable datasets and Clinical Study Reports (CSRs) for all phase 2 and 3 trials by the latter of 6 months after regulatory approval of a new drug or 18 months after the trial’s completion. These proposed timelines are similar to those of the Institute of Medicine (IOM)-National Academy of Medicine (NAM).

Better transparency definitions and implementation are pillars for trustworthiness in healthcare innovation, but it’s also important to note that increasing levels of transparency have opened up other ethics conversations. For example, thanks to enhanced transparency we now know more details about clinical trial designs and enrollments. Stakeholders have noticed that drugs are often tested on younger, whiter, and healthier populations than the patients who ultimately will use a drug after FDA approval.2 Typical patients are often older, sicker, and more ethnically diverse than trial participants. As a result, stakeholders now want to improve trial designs, improve inclusivity in trial enrollment, and use more real-world evidence in drug development.

So, it is tempting to worry that the spouting whale will get harpooned, meaning if we disclose more information, it will expose all of us to more complaints and criticism.

However, criticism isn’t all negative; it actually represents hope. The fact that people are complaining about problems means they recognize that things can be better and the importance of the work being done in drug development. I am confident that BEI and other groups can work together to define what best practices look like and what metrics can be used to track progress over time. After all, what gets measured often gets done. And, implementation and recognition of best practices will be a cause for celebration—no harpoons needed.

References

- Miller JE, Korn D, Ross JS. Clinical trial registration, reporting, publication and FDAAA compliance: a cross-sectional analysis and ranking of new drugs approved by the FDA in 2012. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009758.

- Jin S, Pazdur R, Sridhara R. Re-evaluating eligibility criteria for oncology clinical trials: Analysis of Investigational New Drug Applications in 2015. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3745-3752.

September 14, 2017

Insights on the ICMJE Data Sharing Statement, Part 2

What Transparency Means to Me

Steering Committee Chair,

ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com

When it comes to accessing clinical trial data, for me “transparency” means above all clarity and openness, a willingness and indeed a desire to share data from clinical trials.

I speak as chairperson of the Steering Committee of ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com (CSDR) , which is a group of 13 major pharmaceutical companies dedicated to facilitating greater access to clinical trial data to promote scientific research. As such, I applaud ICMJE’s efforts in support of data sharing.

CSDR has been a leader in the broader movement by pharmaceutical companies and other institutions that fund trials who are together transforming the data disclosure landscape. CSDR offers access to detailed information from clinical trials in ways unheard of just 5 years ago.

By being transparent and inviting researchers to access clinical trial data, CSDR hopes to foster research by giving scientists access to a rich set of data. The fruits from this research, once published, are intended to advance patient care, contributing to medical knowledge more generally.

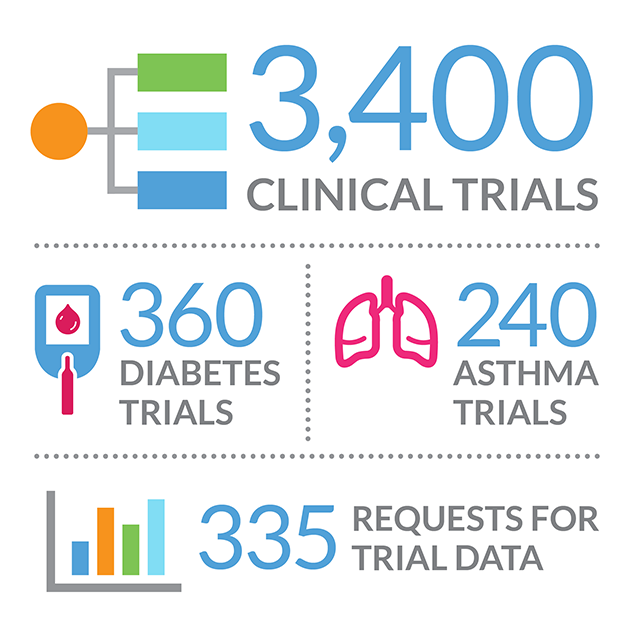

CSDR currently lists more than 3,400 clinical trials and this list is expanding quickly—often as a result of enquiries from researchers. Researchers are encouraged to submit requests for the detailed, anonymized, patient-level data from these trials. They can request access to trials across multiple sponsors, and access is free. Each request is reviewed independently by a process overseen by the Wellcome Trust. On approval and receipt of a signed data-sharing agreement, the data are made available in a secure environment—one that facilitates the research while at the same time preserving the privacy of patients who were part of the trials.

The available clinical trials span a wide range of disease areas. Today there are more than 360 diabetes and 240 asthma trials, for example. So far there have been 335 requests from researchers for trial data. A publication plan is required so that results can be shared broadly. Some results may be published in journals associated with the ICMJE or in other journals that may encourage sharing of patient-level data. Those data may in turn be shared on CSDR—a cycle of knowledge that, in the end, will help inform the scientific community and ultimately benefit patients.

August 3, 2017

Insights on the ICMJE Data Sharing Statement, Part 1

ICMJE Requirements for Data Sharing Statements

Executive Deputy Editor, Annals of Internal Medicine

Secretary, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recently announced a requirement for data sharing statements as a condition for consideration at our member journals of manuscripts describing the results of clinical trials, effective July 1, 2018. In addition, clinical trials that begin enrolling participants on or after January 1, 2019, must include a data sharing plan in the trial’s registration.

By adopting these criteria, ICMJE aims to help fulfill our ethical obligation to trial participants who put themselves at risk on the promise that we will make the most of the information gathered in order to improve clinical care. Although sufficient infrastructure is not yet in place for the ICMJE to mandate data sharing at this time, requiring data sharing statements reflects our commitment to help move the scientific community toward creating the environment in which sharing is expected. ICMJE is excited to engage multiple stakeholders such as Medical Publishing Insights & Practices (MPIP) and the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) in this endeavor.

What Data Sharing Statements Must Indicate

MPIP has inquired about the content of data sharing statements that would meet the ICMJE requirements. Data sharing statements must indicate the following items: whether individual deidentified participant data (including data dictionaries) will be shared; what data in particular will be shared; whether additional, related documents will be available (eg, study protocol, statistical analysis plan); when the data will become available and for how long; by what access criteria data will be shared (including with whom, for what types of analyses, and by what mechanism). Illustrative examples of data sharing statements (including example mechanisms by which data will be made available) that would meet these requirements are in the Table of the editorial announcing these requirements at http://www.icmje.org/news-and-editorials/data_sharing_june_2017.pdf .

It is important to note that the examples provided represent some, but not all, possible statements that would fulfill the ICMJE requirement. These may range from unrestricted, publicly available access to deidentified data without restrictions, to a statement indicating that data will not be shared. The important thing is to be transparent about what will be done regarding each of the items noted above.

How Data Sharing Statements Will Be Evaluated

MPIP also asked how journal editors will evaluate data sharing statements, and how the information provided will be factored into editorial decisions. All ICMJE editors will check to be sure that the data sharing statements include the items outlined above and in our editorial. Although all data sharing statements must address these items, editors may differ in the data sharing plans they find acceptable. Some ICMJE editors already require that data will be shared, as indicated in their information for authors. Others do not currently have such a rule (although they may adopt it in the future) and the degree to which a more or less restrictive data sharing statement will influence editorial priorities may vary. As a general rule, all of the editors would have a preference for plans indicating that data will be responsibly shared. Peer reviewers will see the data sharing statements in the submitted manuscript and, like editors, may vary in the weight they place on more or less rigid data sharing plans when making their recommendations to editors.

Special Situations

MPIP also inquired when it might be acceptable to plan not to share deidentified individual patient data. Such situations might include when it is impossible to adequately assure the confidentiality of trial participants or where national regulations prohibit sharing. As stated above, however, the ICMJE does not currently require that data be shared (although some individual journals may). ICMJE does require a transparent statement of what will be done.